Posts Tagged: Climate Change

When, where and how wood is used impacts carbons emissions

How wood is used after it is cleared from a forest and where that forest is located largely affects the amount of greenhouse gas emissions released into the atmosphere, according to a new study by UC Davis.

The study, published this week in the advance online edition of the journal Nature Climate Change, provides a deeper understanding of the complex global impacts of deforestation on carbon storage and greenhouse gas emissions.

When trees are felled to create solid wood products, such as lumber for housing, that wood retains much of its carbon for decades, the researchers found. In contrast, when wood is used for bioenergy or turned into pulp for paper, nearly all of its carbon is released into the atmosphere. Carbon is a major contributor to greenhouse gases.

“We found that 30 years after a forest clearing, between 0 percent and 62 percent of carbon from that forest might remain in storage,” said lead author J. Mason Earles, a doctoral student with the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies. “Previous models generally assumed that it was all released immediately.”

The researchers analyzed how 169 countries use harvested forests. They learned that the temperate forests found in the United States, Canada and parts of Europe are cleared primarily for use in solid wood products, while the tropical forests of the Southern Hemisphere are more often cleared for use in energy and paper production.

“Carbon stored in forests outside Europe, the USA and Canada, for example, in tropical climates such as Brazil and Indonesia, will be almost entirely lost shortly after clearance,” the study states.

The study’s findings have potential implications for biofuel incentives based on greenhouse gas emissions. For instance, if the United States decides to incentivize corn-based ethanol, less profitable crops, such as soybeans, may shift to other countries. And those countries might clear more forests to make way for the new crops. Where those countries are located and how the wood from those forests is used would affect how much carbon would be released into the atmosphere.

Earles said the study provides new information that could help inform climate models of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the leading international body for the assessment of climate change.

“This is just one of the pieces that fit into this land-use issue,” said Earles. Land use is a driving factor of climate change. “We hope it will give climate models some concrete data on emissions factors they can use.”

In addition to Earles, the study, “Timing of carbon emissions from global forest clearance,” was co-authored by Sonia Yeh, a research scientist with the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies, and Kenneth E. Skog of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service.

The study was funded by the California Air Resources Board and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Cruise to uncover climate change

Tree rings. Ice core records. Cave stalactites. All of these things tell the story of Earth’s history and climate. Now, a UC Davis researcher and others are expanding on that story from the ocean’s point of view. They just returned from scouring the seafloor — digging deep into layer upon layer of mud — to uncover centuries of climate data from beneath the ocean floor.

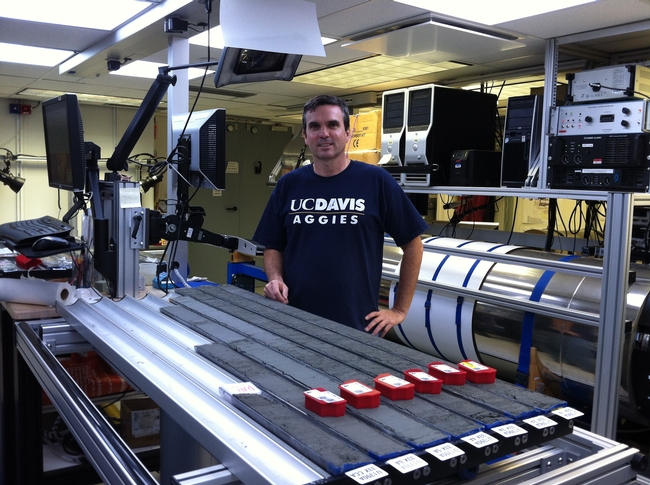

UC Davis geophysicist Gary Acton is one of 34 international scientists that set sail from the Azores Islands on Nov. 17 aboard the drilling vessel JOIDES Resolution. They finished their Mediterranean voyage on Jan. 17, docking in Lisbon, Portugal.

“The climate change recovered at one of the drill sites will be dedicated to providing the most complete marine record of climate change over the past 2 million years of Earth’s history,” said Acton.

The vessel is run by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program and has the unique ability to core into the deepest reaches of the ocean. The IODP Expedition 339 targeted thick sediment drifts that accumulated from warm, salty water—called Mediterranean Outflow Water—flowing from the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar. The researchers drilled, sampled and analyzed the sediment to understand the influence that the MOW water mass has on climate, sea level change and the environment.

“A fascinating aspect of these sediments is their ability to record subtle changes in environmental conditions through measurable changes,” said Acton.

Made heavy by its high salt content, the MOW’s warm waters plunge over 3,000 feet—a drop greater than that of Angel Falls, the world’s highest waterfall—into the Atlantic Ocean. It scours the rocky seafloor, coursing along the margins of Spain and Portugal. Passing Scotland and heading toward Norway, the MOW becomes part of the global conveyor belt that overturns the oceans and circulates water and heat around the globe. Along its journey, sand, silt, clay and microorganisms are deposited along the continental margin as thousands of layers of mud, eventually building into sediment drifts. Each layer contains information about Earth’s history.

“My goal is to reconstruct centennial-scale changes in climate and in Earth’s magnetic field for a time period spanning the past 400,000 years,” said Acton. “Only thick, rapidly deposited sedimentary units like those we are coring provide that ability. They are virtual prehistoric observatories.”

During the expedition, the scientists sailed more than 1,200 nautical miles, drilled 19 holes in 7 different locations, and collected 681 sediment cores—equal to about three miles of mud and sand. Now that the researchers have returned to their homes, they will continue to collaborate as they sift through the data.

“Part of the true value of participating on an expedition like this is the incredible amount of science that can be completed, particularly when scientists with a variety of expertise are confined to a 471-foot-long ship and asked to work 12-hour shifts for two months,” said Acton. “That may seem an odd thing to do over the holidays, but we were all thrilled to be a part of this expedition and to have the chance to continue to work together following the cruise.”

Natural enemy of Asian citrus psyllid coming soon to SoCal

At a Nov. 16 research symposium in Oxnard, hosted by the University of California Cooperative Extension and Hansen Agricultural Center, UC Riverside entomologist Mark Hoddle said that he had completed the testing required to secure federal approval for release of a tiny wasp that preys on ACP, reported John Krist in the Ventura County Star.

The federal government has promised to expedite approval, the article said. Some of the natural enemies - collected in the Punjab, Pakistan - could be carrying the fight against ACP into Los Angeles yards by the end of the year.

Hoddle also said a citrus variety he observed being grown in the Punjab appears able to survive and produce fruit despite the presence of ACP and HLB.

Drought and rising temperatures will challenge California's farmers, experts say

By Suzanne Bohan, Contra Costa Times

In the past century, the state's winter lows have warmed by 2 degrees Fahrenheit, "a significant increase," Dan Sumner, director of the Agricultural Issues Center, told a forum last week. Although that warming trend hasn't yet disrupted crops, it is accelerating, he said. "There's potential for complete crop failure, especially cherries, apricots and other stone fruit," said Louise Jackson, a UC Davis researcher. As an example, Sumner said that as winters heat up, peach growers in the warmer southern San Joaquin Valley may have to move northward, where it's cooler. With California's diversity of crops and different microclimates, the agricultural system has a natural resiliency, although Sumner said now is the time to begin researching ways to best cope with anticipated changes. "I think the risk is we don't take it seriously enough," Sumner said. "The lesson here is you have to have enough research and development to adapt and be flexible. And I don't think we're doing enough."

Health hazards similar in San Joaquin, Coachella valleys

Marcel Honoré, The Desert Sun

A new study on the the environmental health risks across Central California describes conditions strikingly similar to those confronting many eastern Coachella Valley residents. More than 1 million people living in the sprawling San Joaquin Valley face serious health risks from toxic air, polluted water and other environmental factors, according to a University of California, Davis, report published earlier this month.

Food chain holds promise

Doug Ford, The (Vacaville) Reporter

The Solano and Yolo County Joint Economic Summit on agriculture, held at the University of California, Davis, Alumni Center, noted that the area boasts some of the best land and water resources in the world and is ideally located between the populous San Francisco Bay Area and the state capital, with an excellent transportation infrastructure connecting us with world markets. The local "food chain industry," the article said, contributes about 10 percent of the gross domestic product of the area, and its products added up to about $2.5 billion in 2009.

Bravo Lake garden keeps local youths out of trouble

David Castellon, Visalia Times-Delta

Manuel Jimenez and his wife, Olga, spent Black Friday at the Bravo Lake Botanical Garden — the 13-acre public garden and walking trail they helped create about eight years ago — along with a group of teenage boys who volunteered to help.

“The garden is not our goal,” said Jimenez, 61, a University of California Cooperative Extension farm advisor. “Our goal is to grow kids. Our goal is to make something of them.”

Cooling cattle; European pepper moth examined

For an article "Should Wyoming livestock and ag adjust to climate?" in the Billings Gazette, reporter Paul Murray sought information about livestock animals' response to warmer temperatures from Frank Mitloehner, UC Cooperative Extension Specialist in the Department of Animal Science at UC Davis. Mitloehner talked about ways animals can cool down and discussed shade, fans, sprinklers and even alternative cattle breeds. "We're seeing more and more extreme weather. That is a tendency we're seeing more and more often. That can stress animals. Similar to animals in the wild, that can impact animals' reproductive ability and their performance," he told the reporter.

European pepper moth widespread in California

Surendra Dara for Western Farm Press

Western Farm Press published this article about European pepper moth by Surendra Dara, UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor in Santa Barbara County. Dara explains that the European pepper moth has been reported in several central and southern California counties. The pest prefers to feed at the plant base of crops such as corn, peppers, tomatoes, squash, strawberries and some ornamental plants. Dara has been appointed to the national Technical Working Group for European pepper moth, along with UC Cooperative Extension colleagues James Bethke and Steve Tjosvold.

Dara also wrote about this pest and shared photos of it on the UC Strawberries and Vegetables blog.

Bleak future for spring-run Chinook salmon

Warming streams could spell the end of spring-run Chinook salmon in California by the end of the century, according to a study by scientists at UC Davis, the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

There are options for managing water resources to protect the salmon runs, although they would impact hydroelectric power generation, said UC Cooperative Extension associate specialist Lisa Thompson, director of the Center for Aquatic Biology and Aquaculture at UC Davis. A paper describing the study was published online recently in the Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management.

“There are things that we can do so that we have the water we need and also have something left for the fish,” Thompson said.

Working with Marisa Escobar and David Purkey at SEI's Davis office, Thompson and colleagues at UC Davis used a model of the Butte Creek watershed, taking into account the dams and hydropower installations along the river, combined with a model of the salmon population, to test the effect of different water management strategies on the fish. They fed in scenarios for climate change out to 2099 from models developed by David Yates at NCAR in Boulder, Colo.

In almost all scenarios, the fish died out because streams became too warm for adults to survive the summer to spawn in the fall.

The only option that preserved salmon populations, at least for a few decades, was to reduce diversions for hydropower generation at the warmest time of the year.

“If we leave the water in the stream at key times of the year, the stream stays cooler and fish can make it through to the fall,” Thompson said.

Summer, of course, is also peak season for energy demand in California. But Thompson noted that it might be possible to generate more power upstream while holding water for salmon at other locations.

Hydropower is often part of renewable energy portfolios designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, Purkey said, but it can complicate efforts to adapt water management regimes to a warming world. Yet it need not be all-or-nothing, he said.

“The goal should be to identify regulatory regimes which meet ecosystem objectives with minimal impact on hydropower production,” he said. “The kind of work we did in Butte Creek is essential to seeking these outcomes.”

There are also other options that are yet to be fully tested, Thompson said, such as storing cold water upstream and dumping it into the river during a heat wave. That would both help fish and create a surge of hydropower.

Salmon are already under stress from multiple causes, including pollution, and introduced predators and competitors, Thompson said. Even if those problems were solved, temperature alone would finish off the salmon — but that problem can be fixed, she said.

“I swim with these fish, they're magnificent,” Thompson said. “We don't want to give up on them.”

Other co-authors of the paper are graduate student Christopher Mosser and Professor Peter Moyle, both in the Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology at UC Davis. The study was funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.