Posts Tagged: Wildlife

Hedgerows enhance bird abundance and diversity on farms

California’s Central Valley is home to a rich diversity and solid abundance of birds. Many are year-round residents, while others are migrants that winter in our valley or travel to destinations further south. Currently more than 400 species of birds call the Central Valley their home; these include raptors, songbirds, ducks, geese, shorebirds, hummingbirds, and others. (Download a checklist of Central Valley birds here.)

All birds depend on habitat for food, shelter and nesting sites. With a decline in habitat in the Central Valley, primarily due to agricultural expansion, urbanization and water diversions, there has been a significant decrease in the numbers and types of birds. Many bird species are now endangered, threatened or listed as species of special concern. Approximately 36 percent of our state’s historical grasslands, 9 percent of the original wetlands, and 2 to 7 percent of the original riparian forests remain. The Central Valley alone has lost more than 90 percent of the riparian, oak woodland and shrub land habitats.

Despite this loss and fragmentation of habitat, many birds continue to use remnant or restored riparian and upland vegetation around farms. Crops such as rice and alfalfa also provide important habitat and foraging areas for birds. Interest is also surging in restoring lands to enhance habitat for birds, including planting hedgerows of California native shrubs and grasses along field edges.

In a recent study by UC Cooperative Extension and Audubon California in Yolo County, researchers determined that hedgerow plantings along field margins helped increase the abundance and species richness of birds on farms, both for winter migrants and year-round species. Their data analyses, examining farms with and without hedgerows, showed that the presence of hedgerows tripled bird abundance and doubled bird species richness in these linear habitat features, but did not increase the bird abundance in the adjacent crops. Of the 2,203 birds counted during the winter and spring of 2011-12, hedgerows drew 41 species of birds, as compared to 22 species in control areas (weedy, semi-managed field edges). In addition, more than three times as many birds used the hedgerows during wintertime, compared to the spring breeding season. This highlights the importance of this habitat for migrating and overwintering birds.

Of significant interest was the finding that bird pest species were using crops regardless of field edge habitat. That is, crop fields with hedgerows showed the same numbers of bird pest species (such as blackbirds that can damage seed crops), compared to crop fields without hedgerows. The researchers observed a total of 1,642 birds, representing 30 species using the adjacent agriculture fields. The minimal species overlap indicated that a different bird community was using crop fields, regardless of the presence of hedgerows. The researchers also found that crops were more heavily used in the winter than during the breeding season.

Hedgerows provide a variety of ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes, such as attracting native bees to enhance pollination and natural enemies to control pests in adjacent crops. Birds also feed on insects and rodents, potentially helping with pest control in crops. The value of hedgerows on farms for enhanced biodiversity and ecosystem services will hopefully encourage more landowners to establish them on field edges for conservation purposes.

For more information on establishing hedgerows on farms, download the free UC ANR publication Establishing Hedgerows on Farms in California. A more thorough discussion of the study results highlighted in this blog will be published in the upcoming December 2012 issue of the California Society of Ecological Restoration newsletter, Ecesis. A conservation innovation grant from the Natural Resource Conservation Service will help expand and continue this important research.

Poisons on public lands put wildlife at risk

Rat poison used on illegal marijuana farms may be sickening and killing the fisher, a rare forest carnivore that makes its home in some of the most remote areas of California, according to a team of researchers led by University of California, Davis, veterinary scientists.

Researchers discovered commercial rodenticide in dead fishers in Humboldt County near Redwood National Park and in the southern Sierra Nevada in and around Yosemite National Park. The study, published July 13 in the journal PLoS ONE, says illegal marijuana farms are a likely source. Some marijuana growers apply the poisons to deter a wide range of animals from encroaching on their crops.

Fishers in California, Oregon and Washington have been declared a candidate species for listing under the federal Endangered Species Act. Fishers, a member of the weasel family, likely become exposed to the rat poison when eating animals that have ingested it. The fishers also may consume rodenticides directly, drawn by the bacon, cheese and peanut butter “flavorizers” that manufacturers add to the poisons.

Other species, including martens, spotted owls, and Sierra Nevada red foxes, may be at risk from the poison, as well.

“Our findings were very surprising since non-target poisoning from these chemicals is typically seen in wildlife in urban or agricultural settings,” said lead author Mourad Gabriel, a UC Davis Veterinary Genetics Laboratory researcher and presid

ent of the Integral Ecology Research Center. “In California, fishers inhabit mature forests within the national forest, national parks, private industrial and tribal community lands – nowhere near urban or agricultural areas.”“I am really shocked by the number of fishers that have been exposed to significant levels of . . . anticoagulant rodenticides,” said pathologist Leslie Woods of the UC Davis California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory System.

Exposure to the poison was high throughout the fisher populations studied, complicating efforts to pinpoint direct sources. The fishers, many of which had been radio-tracked throughout their lives, did not wander into urban or agricultural environments. However, their habitat did overlap with illegal marijuana farms.

Gabriel said fishers may be an “umbrella” species for other forest carnivores. In ecology, an umbrella species is one that, if protected, results in protection of ot

her species, as well.“If fishers are at risk, these other species are most likely at risk because they share the same prey and the same habitat,” said Gabriel. “Our next steps are to examine whether toxicants used at illegal marijuana grow sites on public lands are also indirectly impacting fisher populations and other forest carnivores through prey depletion.”

In addition to UC Davis, the study involved researchers from the nonprofit Integral Ecology Research Center, UC Berkeley, United States Forest Service, Wildlife Conservation Society, Hoopa Tribal Forestry, and California Department of Fish and Game.

(This article was condensed from a UC Davis news release. Read the full press release and watch a flash video of fishers in the wild.)

Using Lidar to map forest structure and characterize wildlife habitat

UC scientists with the Sierra Nevada Adaptive Management Project (SNAMP) are investigating the uses of Lidar (light detection and ranging) in providing detailed information on how forest habitat is affected by fuels management treatments across a large landscape. Mapping forest structure can illustrate how a forest influences surface hydrology, provides for wildlife and how a forest might burn given certain weather and wind patterns. This research is proving useful in wildlife studies, water quantity and fire modeling and forest planning.

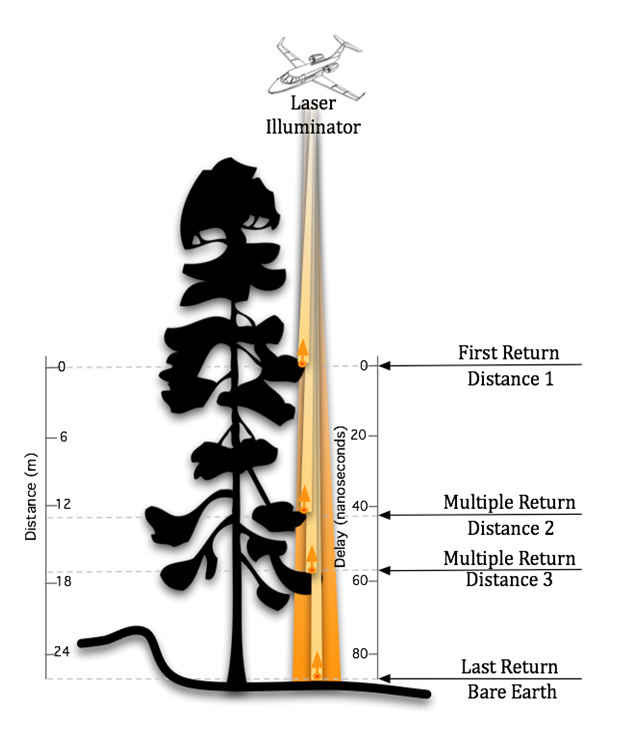

Airborne lidar works by emitting a light pulse from an emitter onboard a plane towards a ground target. A portion of the light is reflected back to the airborne sensor and recorded. The time between sending out the light pulse and receiving it back is converted into distance.

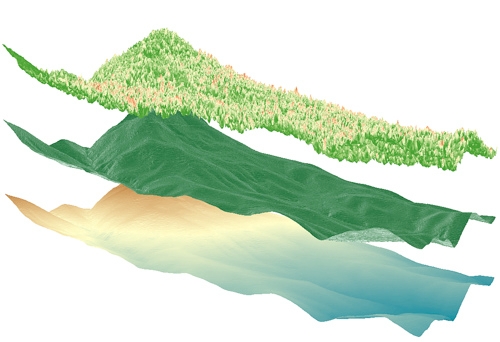

This data, along with GPS information on the aircraft’s exact position and orientation, allows scientists to calculate the height of a target and create 3D maps of the forest vegetation and the bare ground. Raw lidar data is first received as a ‘point cloud’ which consists of millions of points from which meaningful and detailed measurements can be extracted.

Some of the current SNAMP research focuses on developing new methods to detect and delineate individual trees from the point cloud even in complex mixed conifer forests and rugged terrain. The SNAMP spatial team recently published a method that maps all the trees in the forest with 90 percent accuracy. The individual tree identification method identifies trees from the tallest to the shortest and is especially useful in mapping wildlife habitat. For example, the SNAMP spatial and California spotted owl teams collaborated using lidar to map large trees and canopy cover in spotted owl territories. These areas are often hard to identify and map over large areas. Lidar data was used to measure the number, density and pattern of large trees in areas used by the spotted owl. These kinds of data can be used to understand the forest habitat of other bird species and in Pacific fisher research. Below is a short video on the exploration of a lidar point cloud down to an individual tree:

Our goal is to provide methods to map the forest in detail, and thus to help forest managers anticipate the impacts of management decisions.

Images by SNAMP Spatial team/Kelly Labs, UC Berkeley

Biodiversity Reigns Supreme

Biodiversity--that's what it's at on Sunday, Feb. 12 at the University of California, Davis.That's when four museums or centers that engage in...

Senior museum scientist Steve Heydon shows his son, James, 10, around the Bohart Museum of Entomology. (Photo by Kathy Keatley Garvey)

You socked it to us!

Thank you 185 times over!! The wildlife research team from the Sierra Nevada Adaptive Management Project recently put out a request for the donation of single socks. They use them to hold bait for their camera trap studies of the Pacific fisher. The response was overwhelming and the fisher research team would like to thank all of the people who sorted, dropped off or packaged, waited in line and mailed their recycled socks to them. Your commitment and follow through are remarkable!

The team first got bags of socks from the local high school, and then grocery bags of socks started appearing in a local drop off bin. Soon boxes of socks started arriving by mail. They came from all over California and as far away as Oregon, Nevada, Minnesota, Arkansas and Maryland. The boxes just keep coming: 12 one day, 16 the next, 185 at last count!

During one visit to the post office at Christmas time, we had to roll the bin to the car. Other customers standing in line were trying to hide their envy of our good Christmas fortune!

The team has been purchasing socks for years to hang meat in trees to attract the elusive Pacific fisher, a nocturnal weasel, to motion-detecting cameras. Researchers have had to spend valuable time and money acquiring the socks, but never again!

The wildlife piece of this SNAMP forest study continues, along with our other scientific teams, to look at the effects of the U.S. Forest Service’s thinning projects in the Sierra. These projects are done in our national forests for fire protection and forest health. Our scientific research teams from the University of California are here to look at changes these thinning projects bring to the forest, its water cycle and its wildlife. This collaborative effort is part of state and federal efforts to refine management practices for our beautiful and complex forested ecosystems.

We have collected years of baseline data and welcome the forest thinning work that has begun this summer in both the southern site near Oakhurst and the northern site near Forest Hill. We will continue to follow the movements of the fisher over the next few years to learn more about their responses to the forest management efforts.

We have collected years of baseline data and welcome the forest thinning work that has begun this summer in both the southern site near Oakhurst and the northern site near Forest Hill. We will continue to follow the movements of the fisher over the next few years to learn more about their responses to the forest management efforts.

But in the meantime, six newspaper stories and four radio interviews later, we stand in awe of the power of the media and social networks. So, for the many cards, letters and emails we got sharing the stories behind the socks, from the drawers of loved ones who passed away to Earth Day projects for school kids, our wildlife crew is buoyed by your thoughts and support! Our faith in people’s attention to kind details in life is renewed! Thank you!