UC Blogs

Carpenter bees, bee-ing important pollinators

Carpenter bees (Xylocopa spp.) look like bumble bees. The largest in California are the Central Valley carpenter bees (X. tabaniformis orpifex), more than an inch long. The females are solid black, but the males are golden-blond. The males are sometimes nicknamed “teddy bears” because of their soft, burly, and fuzzy appearance. (See the three California species at http://entomology.ucdavis.edu/news/valleycarpenterbees.html).

Carpenter bees nest in soft wood and pithy stems of plants. Nests usually consist of tunnels half of an inch in diameter and 6-to-10 inches deep and may include several brood chambers. Carpenter bees may buzz like saws when constructing nests (hence their name), but they do not eat the wood. Instead, they forage on flowering plants, feeding on nectar, with the females collecting pollen for their offspring. When they have a sufficient plug of pollen in a chamber, females lay an egg on it, and then seal the chamber with woodchips. Another plug of pollen is then added for numerous chambers per tunnel. Development from egg to larva to adult may take about three months. Carpenter bees overwinter as adults, often in old tunnels. There is only one generation a year.

Like other native bees, carpenter bees are important pollinators in native plant communities, gardens, and in some crops. As they visit flowers and feed on nectar, they pick up and transfer pollen. We depend on insect pollination for a third of our food, including fruits and vegetables, nuts (almonds) and seed crops. Insect pollinators such as honey bees contribute a value of around $29 billion to our agricultural industry with about 15 percent of this value coming from native bees like the carpenter bees. Insect pollinators are also important for pollinating wild plants, contributing a food source for birds and other wildlife.

Some people consider carpenter bees pests because they drill holes or nest in wooden structures. However, their contribution to pollination far outweighs any damage to structures, according to native pollinator specialist Robbin Thorp, emeritus professor of entomology at UC Davis. Unlike the eastern carpenter bee species, which can be damaging to wooden structures, our Central Valley carpenter bees choose softer substrates for their nests such as pithy stems of plants, old logs, and untreated redwood. Using untreated, unpainted redwood for arbors, fences and patio or lawn furniture in this area means learning to share with carpenter bees.

So, before getting out your bottle of insecticide spray for controlling carpenter bees, or plugging their nesting holes, think again about their benefits. Thorp considers the use of any pesticides in the hands of untrained homeowners to be a greater risk to their health and safety than carpenter bees ever will be. Carpenter bees nest in his wisteria-covered arbor and he is most happy to live with them.

With a decline in bee pollinators due to diseases, pests, pesticides, stress, and malnutrition, enjoy the presence of these flashy bees, as they are important pollinators.

Equivalent to an Olympic Gold Medal

Walter Leal isn’t participating in the Olympics, but he medaled just the same. It was not for athletic prowess, but for scholarly...

Chemical ecologist Walter Leal. (Photo by Kathy Keatley Garvey)

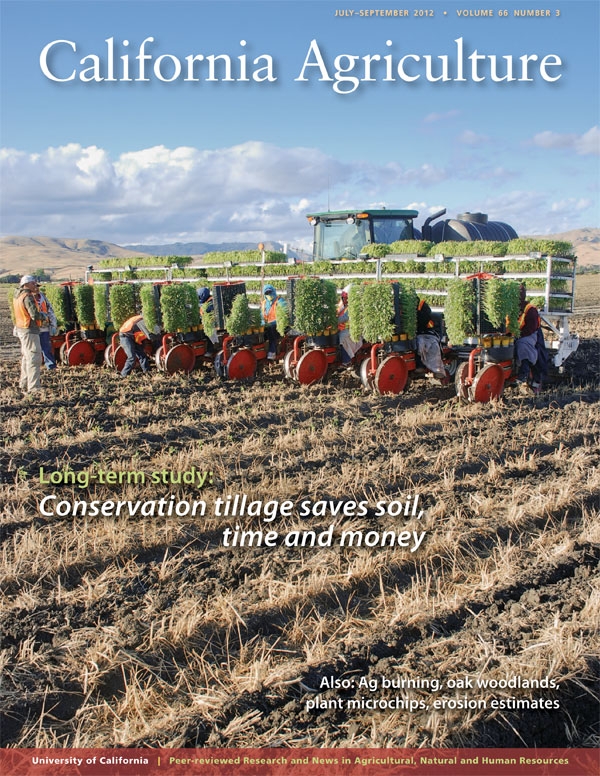

Conservation agriculture involves a systems approach to farming

When delving into conservation agriculture production, it's important to learn the entire system, advises Dino Giacomazzi, a Hanford dairy operator who uses the process to produce corn silage for his cows. Giacomazzi was quoted in a Hanford Sentinel story that focused on research results released in the latest issue of California Agriculture journal. The research concluded that the system works effectively in a cotton and tomato rotation.

In the Sentinel story, Giacomazzi urged local growers interested in undertaking conservation agriculture systems to map out the practice carefully before they start.

“It’s very important for farmers to learn the entire system of conservation tillage from end to end and to know everything they’re going to do for the whole year before they start doing it,” he said. “A lot of failures happen ... when people don’t think the whole thing through.”

Another result of a news release about the new issue of California Agriculture journal was an editorial in the Porterville Recorder praising conservation systems. In the opinion piece, the editors wrote that they often hear farmers are not good stewards of the environment, "but that just isn't true."

"One shining example of being good stewards is no-till farming, a practice that has been around a couple of decades but one that is growing in acceptance," the editorial said.

Giacomazzi, the Hanford dairyman, is a member of Conservation Agriculture Systems Innovation (CASI), a collaborative effort involving UC, farmers and industry representatives that provides information and support to encourage adoption of conservation agriculture practices in California. He presented the keynote address at an event in January that launched CASI, which is available below:

New Strawberry Pest

When we first moved to Benicia, our neighbor gave us some strawberry plants to grace our new raised vegetable bed. Since then, I’ve been the only person in the family who picks them (despite having a strawberry-loving son). But this summer, much to my surprise, I learned that I have competition from an unusual strawberry pest.

Although not identified on UC’s Integrated Pest Management website, Labradorus retrievous (var. yellow) is one of the furrier, larger, garden pests. This non-native species, which occurs throughout California, is quadrupedal with a distinctive rudder-like tail. The tail alone can cause considerable damage at peak rotational velocity. Possessing a large blocky head, but lacking antennae, the species has short whiskers to help it evaluate its environment. It seems drawn to human activity and, in particular, round or plush toys. Although some species have subterranean (digging) tendencies, I fortunately have not seen that particular variety in my yard.

I recently observed a particular individual of the species investigate my raised veggie bed, but I really thought nothing of it—even as it placed its forepaws on the edge of the bed and sniffed at the strawberry plants. Then, suddenly, the individual stuck its head deep in the plants, rooted around, and came up with its prize—a ripe red strawberry—that it promptly gulped down.

This would explain my unusually small strawberry crop this season.

I also have seen Labradorus (var. black) carefully stand on two hind legs and delicately pluck blackberries from a bush. Thus, it appears that this particular garden pest has a proclivity for berries of all types. But given the minimal damage that occurs, and the benefits that this particular species of pest brings to the home and garden, little intervention—other than perhaps a fence for the veggie bed—is recommended.

The beginnings of the attack on strawberries. (photos by Erin Mahaney)

Note the technique at which the pest locates the berries.

Ultimately, the strawberry is devoured.

It's the Nature of Things

The thing about predators and prey is that it's the nature of things. Take spiders. The many different species have different methods of...

Orbweaver eating its wrapped prey, a honey bee. (Photo by Kathy Keatley Garvey)

Two spiders ganging up on a honey bee. One is administering a fatal bite. (Photo by Kathy Keatley Garvey)